Piccola clip per la simulazione di Thesan. Guarda il video nell’articolo qui sotto.

Prendendo il nome dalla dea dell’alba, le simulazioni di Thesan del primo miliardo di anni aiutano a spiegare come le radiazioni abbiano plasmato l’universo primordiale.

Tutto iniziò circa 13,8 miliardi di anni fa con il grande “bang” cosmico che improvvisamente e sorprendentemente creò l’universo. Presto, l’universo infantile si raffreddò drammaticamente e divenne completamente oscuro.

Poi, nel giro di poche centinaia di milioni di anni[{” attribute=””>Big Bang, the universe woke up, as gravity gathered matter into the first stars and galaxies. Light from these first stars turned the surrounding gas into a hot, ionized plasma — a crucial transformation known as cosmic reionization that propelled the universe into the complex structure that we see today.

Now, scientists can get a detailed view of how the universe may have unfolded during this pivotal period with a new simulation, known as Thesan, developed by scientists at MIT, Harvard University, and the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics.

Named after the Etruscan goddess of the dawn, Thesan is designed to simulate the “cosmic dawn,” and specifically cosmic reionization, a period which has been challenging to reconstruct, as it involves immensely complicated, chaotic interactions, including those between gravity, gas, and radiation.

The Thesan simulation resolves these interactions with the highest detail and over the largest volume of any previous simulation. It does so by combining a realistic model of galaxy formation with a new algorithm that tracks how light interacts with gas, along with a model for cosmic dust.

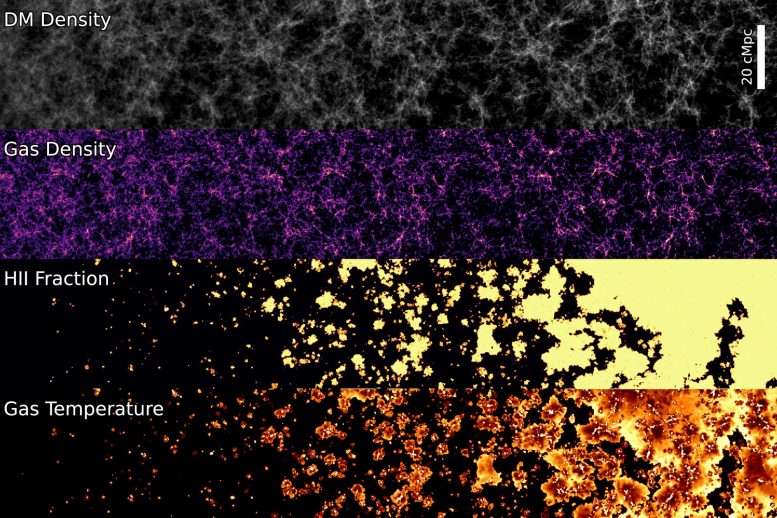

Evolution of simulated properties in the main Thesan run. Time progresses from left to right. The dark matter (top panel) collapse in the cosmic web structure, composed of clumps (haloes) connected by filaments, and the gas (second panel from the top) follows, collapsing to create galaxies. These produce ionizing photons that drive cosmic reionization (third panel from the top), heating up the gas in the process (bottom panel). Credit: Courtesy of THESAN Simulations

With Thesan, the researchers can simulate a cubic volume of the universe spanning 300 million light years across. They run the simulation forward in time to track the first appearance and evolution of hundreds of thousands of galaxies within this space, beginning around 400,000 years after the Big Bang, and through the first billion years.

So far, the simulations align with what few observations astronomers have of the early universe. As more observations are made of this period, for instance with the newly launched James Webb Space Telescope, Thesan may help to place such observations in cosmic context.

For now, the simulations are starting to shed light on certain processes, such as how far light can travel in the early universe, and which galaxies were responsible for reionization.

“Thesan acts as a bridge to the early universe,” says Aaron Smith, a NASA Einstein Fellow in MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research. “It is intended to serve as an ideal simulation counterpart for upcoming observational facilities, which are poised to fundamentally alter our understanding of the cosmos.”

Smith and Mark Vogelsberger, associate professor of physics at MIT, Rahul Kannan of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, and Enrico Garaldi at Max Planck have introduced the Thesan simulation through three papers, the third published on March 24, 2022, in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Follow the light

In the earliest stages of cosmic reionization, the universe was a dark and homogenous space. For physicists, the cosmic evolution during these early “dark ages” is relatively simple to calculate.

“In principle you could work this out with pen and paper,” Smith says. “But at some point gravity starts to pull and collapse matter together, at first slowly, but then so quickly that calculations become too complicated, and we have to do a full simulation.”

To fully simulate cosmic reionization, the team sought to include as many major ingredients of the early universe as possible. They started off with a successful model of galaxy formation that their groups previously developed, called Illustris-TNG, which has been shown to accurately simulate the properties and populations of evolving galaxies. They then developed a new code to incorporate how the light from galaxies and stars interact with and reionize the surrounding gas — an extremely complex process that other simulations have not been able to accurately reproduce at large scale.

“Thesan follows how the light from these first galaxies interacts with the gas over the first billion years and transforms the universe from neutral to ionized,” Kannan says. “This way, we automatically follow the reionization process as it unfolds.”

Finally, the team included a preliminary model of cosmic dust — another feature that is unique to such simulations of the early universe. This early model aims to describe how tiny grains of material influence the formation of galaxies in the early, sparse universe.

Questa simulazione dell’evoluzione del gas e della radiazione mostra un’incarnazione del gas idrogeno neutro. I colori rappresentano intensità e luminosità, rivelando la struttura di reionizzazione incompleta all’interno di una rete di filamenti di gas neutri ad alta densità.

ponte cosmico

Con i componenti di simulazione in atto, il team ha determinato le sue condizioni iniziali per circa 400.000 anni dopo il Big Bang, sulla base di misurazioni precise della luce residua del Big Bang. Hanno quindi sviluppato queste condizioni in avanti nel tempo per simulare un’area dell’universo, utilizzando la macchina SuperMUC-NG – uno dei più grandi supercomputer del mondo – che ha sfruttato simultaneamente 60.000 core di computer per eseguire calcoli Thesan sull’equivalente di 30 milioni di CPU. . un’ora (uno sforzo che avrebbe richiesto 3.500 anni per essere eseguito su un singolo desktop).

Le simulazioni hanno prodotto la visione più dettagliata della reionizzazione cosmica, attraverso il più grande volume di spazio, di qualsiasi simulazione esistente. Mentre alcune simulazioni vengono eseguite su grandi distanze, lo fanno a una risoluzione relativamente bassa, mentre altre simulazioni più dettagliate non coprono grandi dimensioni.

“Attraversiamo questi due approcci: abbiamo un volume elevato e un’elevata precisione”, sottolinea Vogelsberger.

Le prime analisi delle simulazioni indicano che alla fine della reionizzazione cosmica, la distanza che consente alla luce di viaggiare è aumentata significativamente di più di quanto ipotizzato in precedenza dagli scienziati.

“Thesan ha scoperto che la luce non percorre grandi distanze nell’universo primordiale”, afferma Canan. “In effetti, questa distanza è molto piccola e diventa grande solo alla fine della reionizzazione, aumentando di 10 volte in poche centinaia di milioni di anni”.

I ricercatori stanno anche vedendo suggerimenti sul tipo di galassie responsabili della reionizzazione. La massa della galassia sembra influenzare la reionizzazione, anche se il team afferma che ulteriori osservazioni, fatte da James Webb e altri osservatori, aiuteranno a identificare queste galassie dominanti.

“Ci sono molte parti mobili dentro [modeling cosmic reionization]’, conclude Vogelsberger. “Quando possiamo mettere insieme tutto questo in una specie di macchina e iniziare a farla funzionare e ottenere un universo dinamico, quello per tutti noi è un momento molto gratificante”.

Riferimento: “This Project: Lyman-A Emission and Transfer during the Reionization Era” di A Smith, R. Cannan, E. Garaldi, M. Vogelsberger, R. Buckmore, in Sprinkle e L. Hernquist, 24 marzo 2022 Disponibile qui Avvisi mensili della Royal Astronomical Society.

DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stac713

Questa ricerca è stata supportata in parte dalla NASA, dalla National Science Foundation e dal Gauss Center for Supercomputing.

“Giocatore. Aspirante evangelista della birra. Professionista della cultura pop. Amante dei viaggi. Sostenitore dei social media.”